Every morning, as I pour myself a large glass of clean potable water, I thank it as it comes out of my faucet.

Then I feel it as a shape—its texture, density and temperature—as it flows into my mouth and throat and then down inside my torso, merging with my body.

My water comes from our well right next to the house, and as I drink, I imagine my human self merging with the land beneath my feet, connecting me to this particular place and moment in time.

I like this gratitude ritual. And as I fill my teakettle to heat more water, I think about the relationship between the electricity that creates the heat and the water that boils. As I slowly pour hot water over my coffee grounds, I watch the water do its merging thing yet again—pulling flavor out of the beans, morphing into coffee water—a new version of itself.

So adaptable, powerful, and essential. The same water that has always ever been on this planet, constantly morphing, merging, and adapting.

Alchemy

It’s December, and as usual, my activity turns more inward—I hunker down and let myself do a deep dive into something usually fabric or textile-related. Last year, it was all about the unique process of indigo dyeing—learning to create my own vats, experimenting with multiple dips, stitching resists patterns.

There’s a lifetime of learning ahead of me with indigo, but this winter, I’m rounding out my palette and exploring other natural legacy dyes that humans have always used—some for centuries, other for several millennia.

All natural dyeing requires lots of steps and lots of time. And water is a huge part of each one.

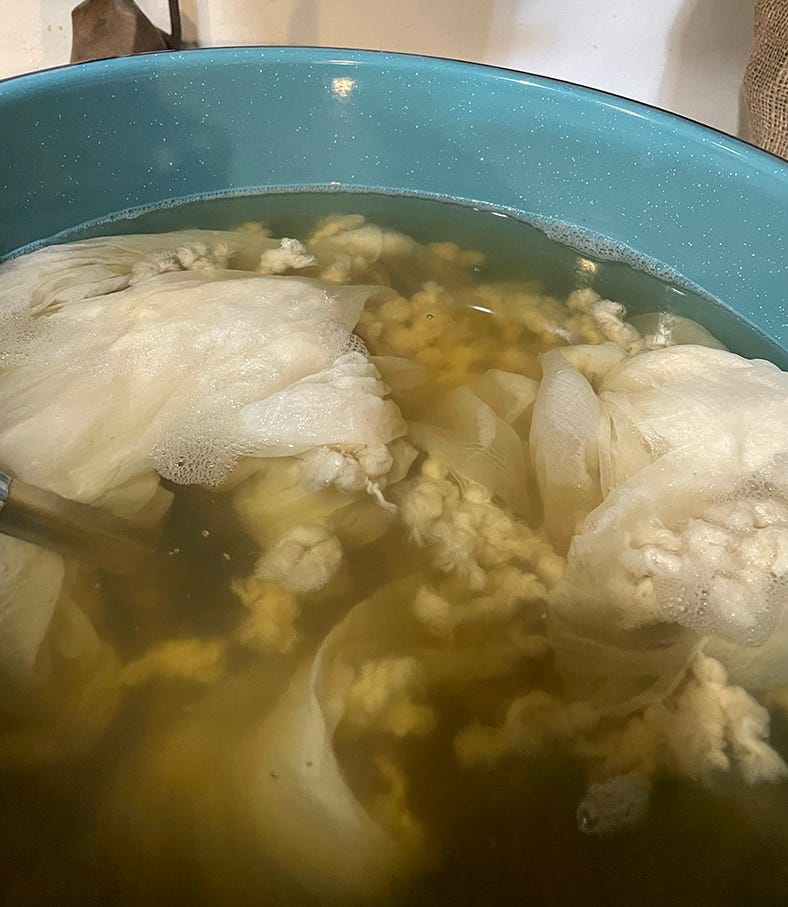

It all starts with scouring the fabric in a huge pot on the stove top to remove contaminants, followed by the mordanting process—soaking in a tannin or alum bath—or both—that helps the color from the plant actually adhere to the fabric. Then finally, there’s the actually dyeing itself.

After what feels like weeks of watching how-to videos and prepping the fabrics, I’m now at the dyeing stage.

As I swirled my fabric samples in their separate dyepots this weekend, I watched the water merge with the dye pigment and then watched that colored water more slowly merge with my fabric.

The nature of one’s water (the PH, the minerals) impacts the color that arises. And as I worked, I felt immersed in an intimate collaboration among me, my Taos water, these ancient plant dyes and time. Understanding the role of time, temperature and the qualities of your own water system is as important as understanding the dye plants themselves.

My first three dye sessions were with Indian madder root, Peruvian cochineal, and marigold (an international dye plant) on two types of woven wool fabrics—one a dense, heavyweight ‘Dorr” wool, and the other, a diaphanous merino. When I’m done writing this post, the next round of dyeing will be with Himalayan rhubarb, Eastern brazilwood, and lac.

Each plant offers up its unique color with a subtle depth and variation that synthetic dyes—which offer more efficiency and consistency—do not.

My water seems to have a touch of iron, which in the parlance of natural dyeing, can “sadden” a color but also deepen it. Having iron in the water makes it hard to produce a clear lemony yellow, for instance, but this doesn’t make my water a problem, it’s just neutral information that helps me know it better. So we’re closer now—my water and I—as I make samples and learn the available dye palette of my unique location on the planet, a palette of color from this particular corner of this particular little mountain town.

Of course, as a gardener, I’m already thinking about what dye plants I can possibly grow here and what I can’t. Which makes me think about the trade on the ancient silk road and the old sea routes—imagining a dyer in medieval Europe creating reds from plant roots from a faraway place called China or India that she’s never seen and never will.

Natural dyeing is slow and time consuming and the magic and deep satisfaction of standing in my dye kitchen watching the color transform the textile is hard to explain. My current efforts are all about understanding the dyes and my water on a variety of fabric types so I can make intentional choices for unknown projects in the future.

It relaxes me to sink into this process, to build a relationship with my dyeing partners both by giving—offering my focused attention to each step and the various tools, materials and elements—and by receiving—joyfully basking in the beauty of the color reward that emerges from this alchemy of water, plant and insect materials, and time.

All process-oriented art and craft forms create an intimacy with the physical world and a more spacious relationship with time that can fill a hole in the lives of a busy, contemporary industrialized culture that many people don’t know they have. I wish they did.

As I rinse my small squares of fabric and hang them to dry, I marvel at the color, imagine the possibilities, and feel glad.

Risograph Prints for Sale

On the opposite end of the art-making spectrum, I took a Risograph class over Thanksgiving weekend. The Risograph was developed in Japan in the 90s as a kind of color office copier that sort of works like a silk screen and prints a bit like an offset printer. It’s feels very retro and has become the cool “all the rage” tool of zine makers and graphic designers.

As a zine maker married to an ex-offset printer, I fantasized about owning one so J. and I went to this short workshop in Albuquerque to investigate. It was fun and I want to do it again, but I’m not sure about owning one anymore. While the look is retro, the machinery is definitely not because of its surge in popularity. I’m on the fence about it as a pricey process.

I did, however, get to make a bunch of 11” x 15.5” prints of one of my drawings called Mexican Dog. I’m selling the 12 of them that worked out. I gave one as a gift, so I have 11 left.

I may make other things with this drawing, but there will never be more “Riso” prints of it like this, so it’s a limited edition.

They are 48.00 plus 7.00 shipping.

Could make a lovely holiday gift, even for yourself!

Here’s a picture:

Interested but have questions first? Just hit reply to this newsletter or DM here on Substack.

(If you live in Taos and want to buy one and pick it up, you don’t have to pay for shipping. However, I couldn’t figure out how to offer that option in Stripe, so please just hit reply or DM me if you want to do this and I’ll send you an invoice.)

Have you done any natural dyeing or Risograph printing? Curious to learn more about either one? Or maybe you too make process-oriented work? Please leave a comment, I’d love to hear. (Or just click the heart button and read the comments if that’s more your style!)

And as always, thank you, thank you for reading all the way to the end.

What a fascinating process. Thanks for sharing it with us. I love how your mind considers the beauty of the process.

Lovely relaxing read. I feel this "Of course, as a gardener, I’m already thinking about what dye plants I can possibly grow here and what I can’t" — as an inner reflection—what can and what can't — always a good shifting. Thank you.

Happy holiday dear Sarah.